To the scale of my mouth

“This is my baby, its name is Teeth.”

I might like a baby made of tree bark, cotton balls, jelly beans, or marbles, but not one made of teeth. It has the same aversion as a baby made of fingernails. I keep teeth around for as long as it takes the tooth fairy to collect them. But maybe I am reading it all wrong and that narrow explanation is not at all what the child was implying, that this baby was made of teeth, only that its name was Teeth, like my name is Cat and my mother’s dog is named Brinkley.“Teeth” was not intended as a descriptor, just an indicator. There is something still, though, about lingering with a name that ends in “th”, part lisp, part hiss.

Teeth are not gross in the ways of boogers, phlegm, ear wax, urine, or shit. They are not excretions, the metabolic, nutrient drained excesses of the body, but they are entirely somatic as material. They are useful, and we actively and consciously put them to use. They are exposed structural material— a unique instance of our body pulling back the curtain to reveal its inner workings, our mouths open to uncover the machine that begins the digestive process. Teeth are amongst the exceptionalities of our mostly flesh covered bodies, counted as accessories, like hair, nails, gums, lip skin. Teeth are mostly attached to us but sometimes they fall out, necessarily or accidentally. They grow back, but only once. In her forties my mother broke part of her tooth on a soft piece of bread. My father’s two front teeth, more square than rectangle, were fake since he was nine, knocked out from fall in a sandbox. No one likes being tilted back in a dentist chair, and breaking or pulling teeth makes most everyone cringe. Unlike bones, they do not contain human tissue. They are more like stones, stronger though, made of calcium and phosphorous. When I am anxious I often dream of having loose teeth.

Our teeth make us living fossils— they begin to fossilize while we are still alive. They are fossilizing now as you unconsciously run your tongue across their subtle, rhythmic topography. Tartar forms plaque that calcifies and traps food, bacteria, pollen. This calcification creates a codex of information for archeologists to study. From tooth-sized history books, scientist can divine how you lived and what you ate, your gender, ancestral background and sometimes individual traits, like if you are an anxious person who tends to grind your teeth, or if you played a particular musical instrument.

Archeologists found traces of blue in the set of teeth of a woman’s remains from the 12th century, buried in a cemetery of a small religious community in Germany. After some study, it was determined that the organic compound of the particles of blue was lapis lazuli, a precious stone worth its weight in gold, imported from a specific region in Afghanistan that was ground and mixed with egg to make ultramarine ink, the true blue on the primary color wheel. In the production of sacred manuscripts, that blue illuminated letters, borders, the robes of kings and saints, and was a special indicator of the Virgin Mary.

There were two explanations for the bits of blue embedded in her teeth. The first: the woman’s job was to grind the lapis lazuli stone into the pigment, and the blue was from years of breathing clouds of dust. The second: the woman was a scribe herself, and the stain of blue came from using her mouth to moisten and shape the tip of the paint brush before putting it to the page. Day by day, stroke by stroke, she painted her teeth blue with a stain that remained for nine-hundred years. It was this second vision that held me, in such a severe way that for a time I forgot there was ever another possibility.

Perhaps it is because I can see the gesture of this unnamed woman’s hand and mouth, moistening lips, pursing mouth around brush and pressing with tongue, in the same way one puts a frayed thread to their mouth in order to put it through the eye of a needle. I remember the taste of cheap, watery paint and the fine haired texture of the children’s grade paint brush I used to paint watercolor pictures with my sisters at the kitchen table on slow Saturday mornings. If you put your own tongue to the roof of your mouth you can find the spot— the nested niche at the top of your teeth where the tip of the tongue naturally rests, against the gum arrow pointing down to doubled enameled arches.

This woman was a scribe, copying letters and illustrating stories of a sacred text that in its time, offered a code for corporeality. She likely spent the body of her days bent over a tilted desk, duplicating and illuminating shapes, colors, and lines, putting brush to tongue and teeth, then brush to paper. Her concentration on the fidelity of the page before her made her teeth a living palimpsest, and in this labor of her monastic life, she was devoted.

Devotions are daily habits for the spirit— like washing the sleep from your face and eyes in the morning, flossing carefully between your teeth at night or taking a brush through wet hair. As a child and teenager I encountered “devotions” as a daily time spent in reflection that could take the form of prayer, journaling, or reading and memorizing scripture. I awoke most mornings of my childhood to my father reading his worn Bible at the kitchen table, hand wrapped around a mug of coffee, writing minuscule notes in a small journal. I often did my devotions at night— it was intended to be a daily practice. Have you done your devotions? Have you eaten yet? Have you brushed your teeth?

Christians often refer to these routine ministrations as “daily bread”. Give us this day our daily bread… To liken this time with God to the sustenance of a meal also references the story of manna in the Old Testament, when the Israelites wandering landless in the desert received a mystical bread called manna each morning. If the Israelites gathered and stored more than what was needed, it would spoil. Provision then, was just enough nourishment for the day— ones daily bread.

I used to memorize scripture. Scripture memorization was held as a high value in my home. “Hiding words in my heart” was meant to bring understanding, comfort, and fullness of life. Words of the Bible have the power to sustain, to do the work of bread and milk and further, satisfy for all eternity. I see it now as a gift to believe in words as food. It formed an openness in to see not just words and symbols, but sounds and gestures, processes and labor, to exist in a field that was two fold, sides of each other, the physical and spiritual.

“‘Son of man, eat whatever you find here. Eat this scroll, and go, speak to the house of Israel.’ So I opened my mouth and he gave me this scroll to eat. And he said to me, ‘Son of man, feed your belly with this scroll that I give you and fill your stomach with it.’ Then I ate it, and it was in my mouth as sweet as honey.”

Transubstantiation is the Catholic belief that the bread and wine of the Eucharist becomes the body and blood of Christ. As an evangelical Christian, I was not raised to believe in that literal transformation, only that it is a really good metaphor for substitutionary atonement— though that cannibalistic sounding practice always thrummed in the curious wings of my mind as I took a tiny cup of grape juice and piece of crushed cracker from the silver communion plate passed down the aisle.

These traditions come from a religious era that was enlivened, not just in the sense that it was energetic, but that spiritual practices were mystically animated with life. The mind and spirit were not so lobotomized from the body, nor were rituals deadened and rote like the factory made communion plate with evenly spaced holes filled with miniature plastic cups. In medieval times, illuminated manuscripts were haptic, intended for human touch, and people conceived their spirituality as being inseparable from the sensual, that which could be experienced through the five senses. It was not an impossibility that the literal words and images before them were as nourishing as bread, or thirst quenching as wine. The books themselves were made from animal skin, vellum, and thus were perceived as a still living entity. They moved and curled with moisture, acting so like a living being that clasps were placed on the sides to hold the vellum down. In the 15th century devotional kissing was popularized. Devotional kissing was a practice of haptic belief, a spiritual exchange orchestrated through touch. Parishioners would kiss the image of the crucified Christ in illuminated manuscripts. We know this because on certain pages, the image of Christ is worn away. Pages are discolored and bear the greasy residue of noses and mouths pressed to skin. A kiss is intimate, offering a moment for the brief intermingling of souls. A devotional kiss was a shared breath with the divine. Touching lips to a page, in a longing and gesture I understand, meant immaterial hope for eternity.

It was offered at one juncture that the woman’s teeth might have been stained from devotional kissing, a possibility dismissed because it was not popularized until three centuries after the woman’s death. Yet there is still this parallel, and perhaps more profound act of touch— not through kissing, but a task of ongoing labor and livelihood, a livelihood also attached to devotion to the text that explained the orders of the universe. She did not leave marks on an object, the gesture of devotion inscribed itself on her. Her spiritual labor was physically inscribed into her body. I fell in love with this woman, who lived so long ago, who had devotion strapped so tightly to her mind, her hand, her time, her teeth.

Since my mom handed me a needle, thread, and square of fabric to make pillows for my dolls, I have made quilts, drawings, weavings, blankets and clothes. It is my first instinct to learn a gesture and repeat it— again, and again, then again. In graduate school I was reading about how the practical function of tapestries was to insulate cold and drafty castles. I sewed hundreds of miniature pillows to make a puffy blanket that hung against and warmed the wall. A faculty member commented that it seemed it was my habit to find a comfortable gesture and become a machine by repeating it. There was a question to his statement, a critique that implied some mindlessness or lack of thought on my part, that I could not answer to at the time. Anni Albers, since, has helped me unwind its complicated boundaries in the thesis that we need material to make sense of immateriality. In her essay Material as Metaphor she writes

“To make it [the invisible and intangible] visible and tangible, we need light and material, any material. And any material can take on the burden of what had been brewing in our consciousness or subconsciousness, in our awareness or in our dreams…Total chaos is not human. In the cosmos we try to unravel the riddle of its order.”

To craft material through labor and repeated gesture is to be able to stand outside the chaos, outside of oneself, and mediate it through a process of being entirely inside oneself. In a way it is devotion, daily prayers, perhaps even more precious because it implies the skilled and constantly attentive, connected mind and hand.

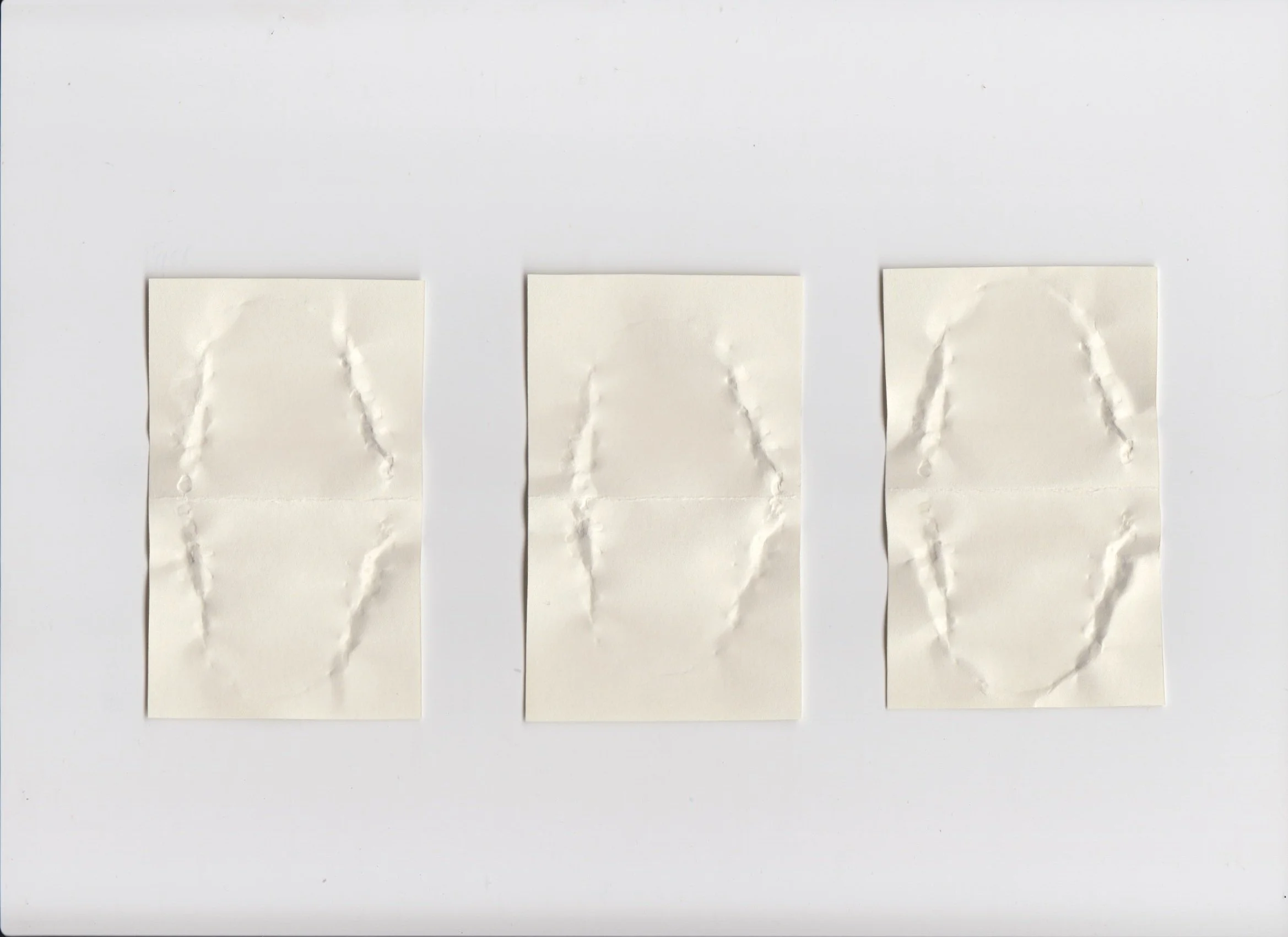

A few days ago I folded a small rectangular piece of paper and fitted it into my mouth. I put it between my teeth and gritted them, side to side, top to bottom. The paper pushed into the creases at the corners of my lips and brushed the back of my throat uncomfortably. I breathed slowly and steadily to keep from the impulse to gag. I wanted to see how I could impress myself into something.

As I ground my teeth into the paper I thought of the woman with the blue stained teeth, gently pressing paint brush between tongue and teeth. We are alike, her and I, the woman with a needle and thread and the woman with lapis lazuli embedded in her teeth, seeking moments of incarnation in the chaos. Like parishioners pressing noses and mouths to skin and inhaling its scent, we use the immanent to access the transcendent. I keep looking to this woman—to teeth and blue calcification, to fossilizing while you are alive and fossilizing when you are dead, to the pattern and grace of a repeated, dedicated gesture. She is body, material, process: sacred, embedded, embodying. For that which is seen, heard, touched, smelled, yes even tasted, serves as mediums of the divine if we pay the right attention.

2019